Books

Civilization

Niall Ferguson

Neil

Ferguson’s blockbuster is essentially a more international PPH course (Politics,

philosophy and History – the Birkbeck course I did

for a year before starting the Medieval History MA) with added economics. From

this you will gather that Ferguson is clever, widely read, opinionated and not

overly modest. His approach is distinctly old-fashioned, as he writes

‘narrative’ history, completely untouched by the likes of Foucault or the other

revered masters of post-modernism; he is devastatingly dismissive of Marixm.

Neil

Ferguson’s blockbuster is essentially a more international PPH course (Politics,

philosophy and History – the Birkbeck course I did

for a year before starting the Medieval History MA) with added economics. From

this you will gather that Ferguson is clever, widely read, opinionated and not

overly modest. His approach is distinctly old-fashioned, as he writes

‘narrative’ history, completely untouched by the likes of Foucault or the other

revered masters of post-modernism; he is devastatingly dismissive of Marixm.

For all the obvious

stereotypes, gross generalisations and lack of nuance, the advantage of this

approach is that it is a hugely enjoyable book to read. The other is that his

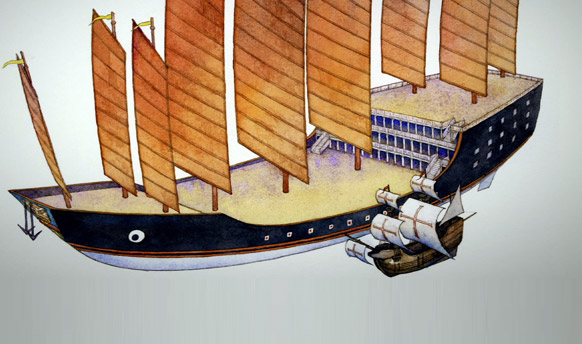

narrative is serious. Essentially, he states (accurately in my view) that in

the late 15th century, Europe was a backwater of squabbling nations

which looked set to be devoured by the Ottoman Empire which could then compete

with the Chinese as to who was the most dominant civilization. In fact, that

didn’t happen; the Ottomans eventually collapsed (but only after being at the

gates of Vienna – and they should have taken the city but for desperate

incompetence) and Chinese Yongle dynasty never progressed.

Ferguson identifies six

features of Western civilisation which he thinks made the difference. In a

solitary example of striking the wrong note he calls these the ‘killer apps’ of

Western states; I shall assume this terminology was foisted on him by Channel 4

as it seems a remarkably un-Ferguson like.

He describes how the Islamic

cultures stopped regarding science as good thing (someone should tell the US

Fundamentalist right about this) and thereafter atrophied under dominant

tyrannical rulers. China closed in on itself, uninterested in the outside

world and failed to build on their achievements. Weapons saw off the indigenous

South Americans, and so on.

A particularly interesting

section was comparing the Anglo-US ‘New World’ with the Spanish ‘New World’.

Why did one flourish and the other not? Here Ferguson believes it was

property rights and a strong law that makes the difference. Immigrants to the

early US earned the right to own land and nurture it for generations, while the

Spanish settlers went to obtain silver and carry away the riches to the

homeland.

In the final section he

suggests that popular belief in the gradual decline of a civilization is

misplaced, and the real model is the demise of the USSR – which collapsed in

just a few weeks in 1989. There is no reason to think that the hegemony of the

West will gently slip away as the East rises. More likely will be a

catastrophic collapse.

But he has good news as

well; the rise of the Chinese and South American economies has been achieved by

their aping Western norms and being better at them. So our civilization lives

on but under a different leadership.

A damn

good book, very readable, provocative and filled with debate.

Freedom

Jonathon Franzen

The reviews of Freedom – and indeed for Franzen himself, have been eulogistic. Apparently he is the

American writer of the moment and can do no wrong. Despite this, I did restrain

myself and wait for the paperback to see what I thought about this new literary

colossus.

The reviews of Freedom – and indeed for Franzen himself, have been eulogistic. Apparently he is the

American writer of the moment and can do no wrong. Despite this, I did restrain

myself and wait for the paperback to see what I thought about this new literary

colossus.

The first great surprise is that it is not an overtly

intellectual book, and doesn’t seem to me to be obviously a critics’ book.

There is none of the pyrotechnics of a McEwan, the

simple writing quality of Roth or the simple cleverness of Barnes. This is, in

fact, a story. The first sentence actually tells the story of the first 400

pages. By the end of page 2 I was completely enwrapped in the tale. If there is

a parallel it is probably War and Peace,

for this is an epic tale of modern American life. And yet, it is also a small

book. It concerns the life of Walter and Patty Berglund, their children and

their best friend Richard. It starts in the 70s when they meet at College, and

it ends in 2010. The book charts the ups and downs of their lives, their

children’s lives and choices and their lovers. The title comes from each

character’s attempts to negotiate their personal freedom.

For their choices are not always good.

Fundamentally, should the Berglunds ever have got

married in the first place, why did Joey settle for his childhood lover, was

Patty right to have absented herself from her parents? But while it is a small

domestic story of a specific family it is always inside the context of America,

American life, American politics. The book almost subliminally charts the ups

and down of the US democratic experience, 9/11 is a mention but always there,

the presidents come and go with support or criticism. When Walter’s lover wants

them to make love in the office Walter sees Clinton and Monica in his head and

can’t do it, while his son briefly hitches his wagon to the Neo-liberal

military industrial complex. But this is never central to the unfolding story,

just a part of the characters’ lives.

While the ending was never clear, it perhaps did

lose a bit of energy in the last few pages towards 600. The protagonists were

tired and no doubt the writer. But this is a page turning classic, a great

story and wonderful portrait of American life.

Babylon Steel

Gaie Sebold

Babylon Steel received a good review in the Guardian and was featured in the Gower

St Waterstones,

which was really nice for Gaie, who is not the

youngest of debut novelists. In fact, I have known Gaie

for about 20 years, since she was a fellow writer at Lewisham’s writing

workshop with Phil Jones. Gaie and I meet

occasionally, usually at a Phil or Charita moment,

turning up at a book launch or some event opening. Being honest,

and I don’t think there is any point being anything but, I was both pleased and

disappointed with Babylon Steel.

Perhaps the first thing to

say is that it is a damned good read, I ripped though it in a few days, and

enjoyed the book. The principal character is the eponymous Babylon Steel,

whore, warrior, good Samaritan and slightly

unbelievable fantasy figure. The world is the Star Wars tavern, one on the cusp

of planes where all races, species and types meet in an atmosphere of money

making and decadence. Babylon runs an up market brothel which doesn’t make ends

meet because she is too kind hearted to both staff and clients. She is sucked

into a complex story involving a young girl trying to make a difficult decision

and go against the wishes of most of her clan and class. There are too many

characters here, too many races and species. And I did struggle with the

dialogue. I am not saying that I could write better banter between a very tall

and gorgeous whore and her reptilian lover, but I suspect less actual dialogue

would have been better!

However there is a second

strand, the story of how Babylon became who she is. I found it a much more

satisfying story. This is the poor and ignorant serving girl plucked by the

Gods to become one of them. But as she learns more of the world of the Avatars,

the less she wants to be part of them. They have trained her as a warrior and a

lover, but she refuses to play the game and tried to destroy these make-believe

gods.

The two stories inevitably

converge, Babylon’s team from the whore house refuse to abandon her as she

takes on the impossible task and all ends (largely) happily.

Overall there are rather too

many good ideas on offer. In this sense it feels like a first novel. I would

suggest that Gaie needs to be more selective over

which ideas to work with, and then make more of each of them. I also felt that

Babylon could have had more moral frailty; I was desperate for her to refuse to

help some suffering misfit and say – Hey, I have a business to run!

However, it should be

remembered that this is hardly my genre – I will be interested to see what

Matthew makes of it, Babylon Steel

was a really good read and highly enjoyable. I look forward to the next one!

See the rave

reviews on Amazon:

For a Night of Love

Emile Zola

I have never really understood Zola. I tried a few

books in adolescence and we suffered a production of the unutterably miserable Therese Raquin

a few years ago and gained no understanding whatsoever. J’Accuse I get, but not quite why

his defence is so iconic so long after the event, so I was not overly hopeful

of gaining insight from three stories occupying just 100 pages. This little

book is greatly helped by a short and insightful foreword by A N Wilson. He

points out that twenty years after these stories were written,

Thomas Hardy was asked to tone down the scene in Tess... when Angel Clare picks up the heroine in his arms and

carries her over a ford in order to spare the blushes of his readers. These

stories, by contrast, are thoroughly modern in their acceptance of female

sexuality and their psychological sophistication. For a night of Love, the story of a beautiful temptress who is also

a sadist who offers a lovesick youth a night of love to collude in her plans.

Complicated, psychological and unpredictable, this is a sexual story of

remarkable modernity. Nantas, tells of a marriage

of convenience leading to extraordinary success made meaningless without love

and sex, while Fasting is an

anti-clerical portrait of a pampered curate and his ambiguous relationship with

his female congregation. This final story a more subtle eroticism wrapped in

satire accompanied by withering observation.

100 pages in total, 100

excellent and revealing pages which do show that Zola was streets ahead

certainly of his ponderous British contemporaries. He is political, sensual,

witty and original. And perhaps worth a measure of revisiting.