Books

Jonathon Strange & Mr Norrell

By Susanna Clarke

This is an extraordinarily long book....

Decency & Disorder: the age of cant

By Ben Wilson

It

is some time since I read a book which was so perceptive about current public attitudes,

the hypocrisy and double standards of celebrity culture and such an informed

analysis of the power of the popular press. Admittedly, this book focuses very

much on England – and really London – between 1800 and 1830, but Wilson’s

choice of time could not be more pertinent.

Wilson’s

subject is the transformation of English society from the freedom-loving,

stroppy, independent minded Georgians of the late 19th Century to

the prim, suppressed and censorious Victorians. It is a revealing book indeed.

The central concept, one provided by critics at the time rather than Wilson, is

cant. A society which so recently prided itself on its openness and honesty

within a single generation become one in which public perceptions were all, and

breathtaking hypocrisy commonplace.

By the mid 1820s there

existed a society which would drive out Byron for writing a great poem but

considered to be without a moral compass, which was re-writing Shakespeare to

make it safe for ‘wives and children’, which spawned organisations like the Suppression of Vice. In 1800 Methodism

was an extreme, rather fringe cult, but by 1820 the King and aristocracy

willingly went to hear their own activities righteously condemned. But the

cant? Well, the campaign to drive from the stage the greatest actor of his

generation, Edward Keane, for his immoral sexual activities, was led by the

editor of the Times, a man who lived with another man’s wife. The secretary of

the Mendacity Society was discovered

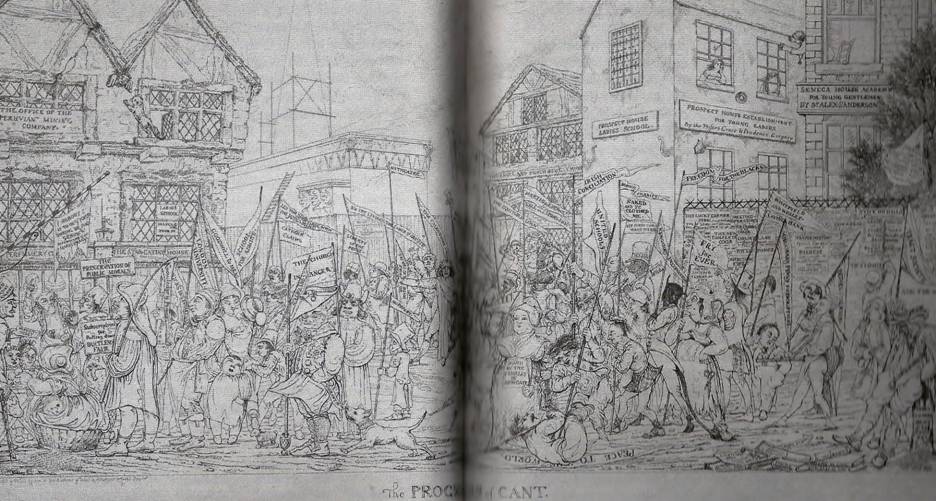

to have his hands firmly on the proceeds, and so it goes on. The whole sickness is summed up by the

wonderful Thomas Hood cartoon, the Progress

of Cant which would take a day to analyse but is full of characters we know

all too well today – a crippled beggar has been issued Mendacity Ticket to exchange

for food’ a Quaker wears a dress made by the female prisoners at Newgate yet

seems to be rather less moral in her own appearance, a fat boy is about to buy

a pie with the money he has collected for charity... the picture is crammed

with grotesques mocking the hypocrisy of the day.

By the mid 1820s there

existed a society which would drive out Byron for writing a great poem but

considered to be without a moral compass, which was re-writing Shakespeare to

make it safe for ‘wives and children’, which spawned organisations like the Suppression of Vice. In 1800 Methodism

was an extreme, rather fringe cult, but by 1820 the King and aristocracy

willingly went to hear their own activities righteously condemned. But the

cant? Well, the campaign to drive from the stage the greatest actor of his

generation, Edward Keane, for his immoral sexual activities, was led by the

editor of the Times, a man who lived with another man’s wife. The secretary of

the Mendacity Society was discovered

to have his hands firmly on the proceeds, and so it goes on. The whole sickness is summed up by the

wonderful Thomas Hood cartoon, the Progress

of Cant which would take a day to analyse but is full of characters we know

all too well today – a crippled beggar has been issued Mendacity Ticket to exchange

for food’ a Quaker wears a dress made by the female prisoners at Newgate yet

seems to be rather less moral in her own appearance, a fat boy is about to buy

a pie with the money he has collected for charity... the picture is crammed

with grotesques mocking the hypocrisy of the day.

This

change of public attitude was a triumph of the middle class, whose values of

abstemious hard work were deemed to be responsible for making the country

great. As Archibald Allison put it: Why

are the middle classes wealthy? Because they put a bridle on licentious

appetites; because they restrain present desire from a sense of future benefit;

because they sacrifice sensual gratification on the altar of domestic duty.

As Wilson puts it, Middle class ambitions

and economic activity were elevated to things of religious worth, they were

rewarded by God for their forbearance and resistance to temptation.

It

occurs unbidden that the New Labour Government was itself a mini Age of Cant. A

government, one of whose aims was to eradicate child poverty, declared that it

was comfortable with wealth, which created ASBOs to put people in prison for

their social menace whether or not they had broken any law, which introduce

mass moral panics culminating in the ubiquitous CRB check (a certificate of

appearances if ever there was one), and which made its ministers richer than

any previous administration. Bowdlerisation of the language of public services

mean we exist in a world of challengers, populated by learners, PSA targets,

and the language of management gurus.

Superbly

written, never dull, full of fascinating facts, Wilson presents a complex yet

coherent picture, a shift in society across the period of Waterloo which has

never been fully reversed. This is a fabulous history book.

The Human Stain

Philip Roth

I

am unhappy with the idea of best of, favourites, top tens. Yet such juvenile

concepts seem to be assaulting me at present. Just after having to decide if London

Assurance was the funniest play I had ever seen, I now have to

decide just how good The Human Stain

is. For now let us just settle for masterpiece and see if that helps.

I

am unhappy with the idea of best of, favourites, top tens. Yet such juvenile

concepts seem to be assaulting me at present. Just after having to decide if London

Assurance was the funniest play I had ever seen, I now have to

decide just how good The Human Stain

is. For now let us just settle for masterpiece and see if that helps.

Like Exit Ghost –

reviewed below – The Human Stain features

Nathan Zuckerman, a writer who lives in New England and suffers from a range of

difficult complaints common to the elderly, including incontinence and

impotence. He is not a well man. Zuckerman, a complex alter ego of Roth (I

assume) has retreated to the countryside, to write and to not commune with

people. He has no desire for human company in these final years. Company,

however, arrives in the form of Coleman Silk, Classics professor and former

Dean of Athena, a small, largely white university. Silk is distraught. He has

just buried his wife and blames a dispute he has been having with the college

for her death. He demands that the novelist write the story of the injustices

done to Coleman Silk. From this unpromising beginning, Zuckerman does indeed

become a friend of Silk, although he steadfastly refuses to write his story.

Although, The Human Stain is

Zuckerman’s story of Coleman Silk.

The injustice is a classic case of Political Correctness. Having

relinquished his Deanship he is back as a teacher of classics when he referred

to two non-attending students as ‘spooks’ as in ghosts. The non-attenders were

black and protested that Spooks was KKK language. Silk refused to apologise,

his enemies gathered together and he resigned in pique and anger. The people he

brought in didn’t back him and he was not invited back by colleagues who

realised the folly of their ways. A shocking waste but a not unfamiliar story.

This tale of local morality is played out against the backdrop of the

impeachment proceedings against Bill Clinton for the Monica Lewinsky affair,

and Roth (if not Zuckerman) invites us to find the parallels. Eventually Silk

realises that his wish to write a hot headed condemnation of his erstwhile

colleagues is a hopeless task, and it transpires that this is largely because

he has fallen in love, or perhaps in lust, with an illiterate cleaner at the

college who is a third his age.

His enemies get wind of the affair and he receives threatening letters,

and it hardly helps that the woman’s ex-husband, a Vietnam veteran who never

recovered, habitually tries to hurt if not kill her subsequent lovers. After

the couple’s death, Zuckerman uncovers the story of the real Coleman Silk, more

improbable and astonishing than anyone can imagine, and writes the posthumous

book that Silk certainly would not have wanted him to write.

This is a difficult and uncompromising book from a writer at the absolute

height of his powers. It is a complex narrative, a well told story that

actually does pull you along. Superbly written he drops hints, he leaves clues,

he teases and entices. But he is a powerful intellectual. He assumes you have a

broad knowledge of the classics so you can follow the illusions of Silk and

about Silk, that Zuckerman writes, that you understand the history of the black

and Jewish people of the States, understand the bitter divisions caused by the

Vietnam War and have a deep familiarity with the issues around the Clinton

presidency. The fashions of liberal academia, the feminist and post modern

agendas are a focal issue of the story, and for me the biggest challenge; a

deep understanding of what it means to be black in the USA. The challenge to

Coleman Silk was always that of being Black. It was simply that no-one ever

asked the right question.

Juliet Naked

Nick Hornby

Nick Hornby has always had a good grasp of blokish topics, notably

football and music, and if you follow him though his oeuvre he displays an

increasing confidence in the emotional issues which affect (ever less younger)

men. It is quite clear that while I have been away, he has got better. Juliet Naked is an excellent book, a

first-class read and far better than I ever expected Hornby could write. In the

week it took to read, I almost missed my stop virtually every day, so enwrapped

did I get with his plot line. We are, as you probably know, back in the world

of music, perhaps one closer to my current experience than even the second hand

record shop, because we so often find ourselves these days at gigs performed by

men older than us, in small venues and surrounded by devoted acolytes. Tucker

Crowe, touring in the wake of his seminal album Juliet quits mid tour and is never seen again.

The book explores what might happen when this mysterious cult hero

actually meets his fans, or at least a couple of them. That this happens in

Humberside rather than London, that it is the girlfriend (ex) of the groupie

and that he is accompanied by his 6 year old son shows just how many surprises

Hornby has in store. Neither Annie nor the reclusive Tucker is in the least bit

stereotyped, but are living, real characters, albeit confused and troubled.

Tucker is a loser, harassed by ex wives and children he has never known, and

even his single success, his youngest son, is a difficult, confusing and

troublesome relationship. Annie has wasted 15 years of her life drifting

through a non-relationship with an obsessive in a small dull part of the

country. She has no idea what is even attainable anymore. She is lost,

depressed, confused and wondering if life has passed her by. Only the music fan Duncan fails to convince

as a character, belonging strictly to the stock male obsessive fan cartoon

character. The world Hornby creates, with its forums and webs, conspiracy

theories and convinced alternative history is compelling. When Duncan finally

meets his lifelong hero he has compiled a list of questions to test his

identity. Instead Tucker shows him his passport. It is a wonderful illustration

of the different worlds they inhabit. Meanwhile Annie struggles to work out why

she is in the small town, and what horizons and ambitions are realistic in

provincial UK. Funny, clever, entertaining and not without its insights, Juliet Naked is a recommended light

read.

Among the Dead Cities

A C Grayling

Mr Grayling certainly does knock out books at a prodigious

rate, and I see with some shock that this dates back to 2006, back in fact to

the brief period when I was in his Introduction

to Philosophy class at Birkbeck.. In this book AC attempts to give a definitive

view on the moral legitimacy of the ‘area bombing’ (as opposed to strategic

bombing) of Germany by the British in 1943-45 and by the Americans in Japan in

1945. Interestingly, for Germany, he singles out the 1943 ‘Operation Gomorrah’

attack on Hamburg, which also features prominently in Witnesses

of War (see

below).

Mr Grayling certainly does knock out books at a prodigious

rate, and I see with some shock that this dates back to 2006, back in fact to

the brief period when I was in his Introduction

to Philosophy class at Birkbeck.. In this book AC attempts to give a definitive

view on the moral legitimacy of the ‘area bombing’ (as opposed to strategic

bombing) of Germany by the British in 1943-45 and by the Americans in Japan in

1945. Interestingly, for Germany, he singles out the 1943 ‘Operation Gomorrah’

attack on Hamburg, which also features prominently in Witnesses

of War (see

below).

Grayling

first sets out ‘the facts’ many of which were new to me. He details the early

attempts to establish the legitimacy – or illegitimacy - of aerial warfare

starting back in 1899 with rules on throwing bombs out of airships or balloons.

Unfortunately the great powers were reluctant to endorse any restriction on the

use of air power because they found it so useful for dealing with their

colonies. Nonetheless, it is clear that there were arguments in all countries

which recognised the arbitrary power of this new weapon and that there was an

attempt to find ways of redressing its potential impact on civilians

(non-combatants). When war was declared, the British were careful to state

that they would use bombers only on military targets and would try to limit

civilian casualties. This was partly in the hope that Germany would in return

minimise its own bombing of the UK. This strategic policy was overturned

in 1942 when it became clear that for the RAF, hitting precision targets was

simply too difficult. The lack of accurate aiming sites, bad weather and the

harrying by German fighters all contributed to strategic bombing being a

failure. The change of tactic to area bombing could, therefore be seen as

simply recognising a de facto

necessity.

Or

not. Throughout the period the USAAF only

bombed precision targets in daylight raids. It was an horrendous policy in

terms of losses to both aircraft and their crew. In contrast, Sir Arthur Harris,

popularly ‘Bomber’ Harris, famously had a clear belief in the efficacy of mass

bombing of civilians as a tactic to win the war, though it is clear from

contemporary quotes, that his peers thought him delusional at best.

Grayling

examines the arguments put forward for area bombing, that they represented a

way of carrying the war to Germany, that it tied up enemy anti-aircraft

personnel and weaponry and that it would destroy the spirit of the people of

Germany. He finds little evidence to support any of these. In particularly the

idea (which, as Stargardt points out below, was shared

by German high command) that bombing would ‘break the morale of the Germans’

was spectacularly wide of the mark. Harris would doubtless argue that only in

the final weeks of the war was he able to heap sufficient damage on the cities

of Germany to crush morale – but of course, the war was essentially over by

this point.

The

book hardly keeps you in suspense as to its final conclusion. From half way AC is

struggling to find defences to ‘balance’ the picture. By showing the doubts the

war time leaders had for the policy, the opposition from leftists such as Vera

Brittain (whose pamphlet Seeds of Chaos:

What mass bombing really means was a surprise best seller), the opposition

from the English bombed-out cities (Those from Coventry and other heavily

targeted cities wrote to papers, MPs and even Churchill demanding that the

allies NOT follow this route) the lack of any objective evidence of the advantages claimed for the tactic and

the astonishing, appalling litany of the victims (listed in an appendix: 1943 -

Wuppertal May 29, 3,400 dead, 130,000 bombed out, Krefeld 21 June, 1056 dead,

72,000 bombed out, Cologne 28 June, 4377 dead, 230,000 bombed out, Hamburg 25

July, 35,000 dead, 800,000 bombed out, Berlin 23 August, 900 dead, 103,000

bombed out and later in 1945 - Magdeburg 16 January, 16,000 dead, 190,000

bombed out, Dresden 13 February, 30,000 dead, 250,000 bombed out, Gladbeck 24

March, 3,000 dead, 40,000 bombed out), it must surely be one of a moral

philosopher’s easier jobs to find that there was and is no defence for the

perpetration of this war crime.

Where

perhaps he has glossed over his responsibilities is in declaring that there is

no question as to the overall morality of conducting World War II. Clearly keen

to distance himself from a pacifist stance, Grayling seems to me gloss over a

rather more complex – and interesting – series of questions. The 2nd

World War may well have been a ‘just’ war, in that Hitler was a fittingly evil

subject to go to war against, but the results of the war were rather more

dubious for those who happened to find themselves in places other than an

offshore victorious nation. Not only was the death toll calamitous – and for

the first time more civilians died than those in uniform - but there were also

massive displacements of populations, and thanks to some thoroughly immoral

politicking between the victorious allies, many millions of people were

forcibly shipped into captivity after the war was over. Perhaps more of the

population of Europe ended up living under totalitarian regimes at the end of

the war than at the beginning and the populations of Germany, Poland and Russia

in particular were subject to appalling mistreatment and arbitrary cruelty.

Personally I think an examination as to whether any war can be morally defended

– and if any war can it was that against Hitler – would have exercised AC’s

brain to more interesting results.

Perhaps

most telling are the asides. ‘Once the US entered the war, adding its

industrial and population resources, the end result was never in doubt’. This

‘moral’ war was really a matter of counting the industrial and agricultural

resources and the sheer numbers of their respective populations who could be

put to work/fight. Had the US kept out, Germany would have won. The only

military decision of import was probably Hitler’s when he launched his suicidal

attack on Russia. That probably finished things off for him. The result of any

war is not dependent on moral values, fighting prowess, the much vaunted

national character or morale of populations. It is decided by the bean counting

of resources. I can think of no categories in which war is the right way of

solving any crisis on any scale. Might does not mean right even though we

happen to have been lucky enough to have had more beans than Germany in the

last two counts.

But

the population of Europe surely lost.

Ordinary Thunderstorms

William Boyd

Two of my favourite books of the last few years (admittedly, of rather

more restrained novel reading) have been by William Boyd. Restless was a superb thriller coming from an entirely original

angle (a mother slowly explains her war-time espionage to her grown-up daughter

before a final resolution of betrayal) and Any

Human Heart is just one of the most wonderful, life-enhancing, brilliantly

constructed books of all time. Ordinary

Thunderstorms is again a thriller coming from an unexpected angle. Having

opened with an account of thunderstorms from a meteorology text book, telling

us that ‘even ordinary thunderstorms care capable of mutating into super-cell

storms’ we go on to hear of just such an analogous mutation. Adam Kindred

almost has it all. Young, rich, a successful climate scientist already an

American professor is in London for a job interview. His first failure has just

happened, his marriage dissolving after a stupid infidelity with a student.

Hence his decision to return to England and start again with his glittering

career. A chance encounter in a cafe leads to his being implicated in murder.

Seeing how bad the circumstances look he does not go to the police immediately

and finds that the murderers are after him next. He decides his only chance is

to disappear, go underground and hope the investigation finds other suspects.

Later a woman who befriended him is murdered and he himself actually does

murder a fellow homeless person.

As well as Adam, the book follows the story through the CEO of a drugs

company, the heart of the conspiracy, Jonjo, the psychopathic killer and Rita

the police officer who discovered the murder. All are interwoven in this

complex plot which really was un-put-downable at times. I read the 400 page

book in less than a week and it was excellent. But not, perhaps as satisfying

as I had hoped.

Firstly, I was not convinced by Adam. Thew book follows his extraordinary

change from his Ivy League start, but I struggled to believe it. There is no

suggestion that he was a TA recruit or even a boy scout, yet this privileged

academic used to the high life in the States rapidly adapts to living rough

with great success. On the other hand he has a file, given to him by the

murdered man, which he knows must be a part of the mystery but it is weeks

before he applies his formidable intelligence to trying to work out the meaning

of the mystery. Finally, having found an alternative identity, would he really

start an affair with a police woman? I found all this hard to take. Similarly

Ingram, the pharmaceutical CEO is a rather pathetic wimp. Perhaps there are

leaders of businesses turning over billions who are not the ‘masters of the

Universe’ we may suppose, but Ingram’s deep uselessness was very difficult to

believe. I should say, however that the psychopath was incredibly well drawn

and scarily believable. He had killed dozens of people over the years but was

unable to kill his own dog. And the other great plus point is that it is a

superb book for charting contemporary, delving into corners not usually written

about full of people who are entirely believable on the margins of society.

The final problem is perhaps the most serious. The plot was good, but

just a touch predictable. Perhaps I have read too many of this rather popular

genre of late, but I was generally 150 pages ahead of Kindred, another reason

why I found it difficult to quite believe in him. It was very clear what the

cause of the murder was, who was responsible and how Kindred could escape, but

it did all take rather a long time to resolve. Admittedly the actual ending is

well crafted and not quite what you might expect, but I expected a few more

real twists and turns rather than the predictable ones we got.

So yes, a really good read and thoroughly enjoyable, but not quite as

great as some of his other recent work.

Witnesses of War

Nicholas Stargardt

The purpose of this book is to examine the

fate of children – all children – living in Germany and the extended Reich

during the second world war, as far as possible through children’s own writing

and drawing. As such I am sure it is an extraordinarily important piece of

work. For me, however, it yet again exposed my deep ignorance of the war, and I

was as focussed on the experiences of the adults under this chaotic, barbaric

and inhuman regime as the children. I was also fixated by the numbers, which

when compared with anything we look at today does put things in perspective.

The purpose of this book is to examine the

fate of children – all children – living in Germany and the extended Reich

during the second world war, as far as possible through children’s own writing

and drawing. As such I am sure it is an extraordinarily important piece of

work. For me, however, it yet again exposed my deep ignorance of the war, and I

was as focussed on the experiences of the adults under this chaotic, barbaric

and inhuman regime as the children. I was also fixated by the numbers, which

when compared with anything we look at today does put things in perspective.

The main characters in this book are 14 children who have left diaries or

letters – they include 8 Germans, 5 Poles and a Czech, 6 of whom are also

Jewish. Most did not survive the war. He also uses Children’s drawing, most

importantly those that survive from a Polish ghetto at Theresienstadt. Some of

this results in quite difficult reading.

The approach is broadly chronological. Stargardt’s suggests that children

were central to the Nazi project, since the aim was to create a racially pure

Germany, something which would only be successfully seen in the next

generation. This work began early, not with Jews, Poles or Roma but with problems

within the German racial stock. The first concentration camps were set up

before the war for the ‘re-education’ of German youth. This is strictly Daily

Mail territory, the Nazi packing off the work-shy, the communists, the

agitators to learn the ‘values of hard work’ and was a policy which carried the

overwhelming support of the German people. Many (how New Labour is this?) had

not committed crimes, their re-education being conducted for ‘preventative

purposes’. These regimes were tough, the discipline brutal and physical, food

scarce and bullying rife. Getting out of these institutions was hard and to

some extend random with governors looking for children to have accepted without

fault the Nazi dogmas and display intense patriotism. In 1935 over 100,000 young

people were in these concentration camps, more than our current (overcrowded)

UK prisons. But it was not just the trouble-makers and individualists who did

not fit with the Nazi image of German racial purity. The physically less than

perfect didn’t either. German youth were to be ‘as tough as leather, as hard as

Krupp steel and as swift as greyhounds’. While policies of sterilisation and

abortion could eliminate the weak, infirm and the ‘idiots’, this would take

time. Action was needed more swiftly to remove those who could not contribute

to the war effort or who did not conform to Nazi racial stereotypes. The campaign of murdering disabled or

mentally ill children and adults started slowly and proved an ideal testing

ground for the technology used in the ‘final solution’ later in the war. It is

often said that the Germans practiced euthanasia, but on this evidence that is

a misnomer. It was simply murder of those deemed not fit to be a ‘proper’

German. Unlike the later death camps the authorities had to act with caution

when murdering their own citizens. A myth of caring was given to parents, few

of whom were suspicious of subsequent unexplained deaths. Those living near the

sanatoriums however were deeply suspicious, and the use of the same coffin for

funerals (it had a hinged bottom allowing the body to be dropped into a grave)

alerting the locals at Idstein. Stargardt estimates that there were about

300,000 victims in this campaign.

Once Poland had been assimilated, the Nazi regime set about one of the

most remarkable programmes of migration ever seen in Europe. The remaining

German Jews were transported out of Germany, and this book largely concentrates

on the fate of those who settle in the ghettoes of Lodz and Warsaw, but ‘Reich’

Germans were sent to take over Polish farms and property, ethnic Germans also

sent to Poland from other parts of the expanding empire and Polish ethnic

Germans were transported away from the Soviet occupied part. In the midst of

this ethnic mix there was also a religious divide, with the Germans being

predominantly Protestant, the Poles’ Catholic and then the Jews. The Nazi’s

were very good at hierarchy and this was a complex one. If Polish Catholics

were next to bottom it did not prevent them taking it out on the clear bottom

of the heap, the Jews. Not that there aren’t myriad stories of brave humanity

as individuals risked all to shelter and save Jews; but equally, petty

vengeance meted out by Poles in the hope of gaining respect in Nazi eyes. The

longest section of the book shows life in the ghetto through the eyes of the

children, and chilling and desperate it is. Stargardt looks at how children’s

play mimiced the horrific world around them, and the oldest, biggest and most

confident boys get to play the Germans. Yet the children were also the black

market runners, often the breadwinners of their families, brushing past bodies

and challenging the guns of their oppressors.

The overwhelming feeling I had from reading this book was the capricious

nature of life and death. When the ghettoes are cleared, the leaders of the

community as well as the beggars and the black marketers were led onto the

trucks, those who survive were simply lucky. There was no reason for death or

survival. Much of the surviving evidence from Auschwitz comes from the ‘Family

Camp’, a humane area kept by the Nazis in the expectation of an International

Red Cross visit. It was the fig leaf for the international community. Groups of

Jews travelling between cities in Poland might be forced to dig their own

graves, lines up and shot. Or not. An account of the murder of 90 young

children in the small Ukrainian town of Belaya Tserkov is particularly hard to

take, though there is something of a hero as the army commander (Lieutenant

Colonel Groscurth) desperately tries to find allies to prevent the massacre.

When the speed of the Russian advance takes the Germans by surprise they

attempt to destroy the evidence of the camps, and force march the surviving inmates back into Germany. Those

that can’t keep up are shot.

The final chapters throw the focus back on the German children, the Nazi

youth. The flower of the Nazi regime, the supposed beneficiaries of the Nazi

programme of racial purity become the last defence against the Russians. Having

been subject to Nazi propaganda throughout their adolescence these are the true

believers. As their fathers and uncles throw their guns away, burn their

uniforms and melt into the chaotic background of Berlin, the Nazi Youth want

death and glory. It is often their mothers who pull them out of the battles and

forcibly rip their insignia from them.

One of the unanswered problems with the war is the attitude of ‘ordinary’

Germans. It is often assumed that the racist policies were only really held by

the ‘Nazis’ not the ordinary German. There is certainly plenty of evidence that

the German army found the aims of the Party either abhorrent or ridiculous, but

the suggestion from this book is that the young in particular really did fall

in line with Nazi thinking. A young German student wrote after assisting the SS

in evicting a group of Jews: Sympathy for

such creatures? No, at most I felt quietly appalled that such people exist who

are in their very being so infinitely alien and incomprehensible to us that

there is no way to reach them. For the first time in our lives, people whose

life or death is a matter of indifference.

The only time contemporary letters and diaries acknowledge the

atrocities is when the Germans feel under threat. When the first mass bombings

are made the inhabitants of the Ruhr worry that they are now paying the price

for their treatment of the Jews, and a similar reaction is heard in the eastern

regions – though obviously it is the German treatment of the Russians which

scared them most. When confident, however, there seems little trace of remorse

or worry apart from the tiny number who were committed opponents of the regime.

A frequent observation is that the concentration camp prisoners, prisoners of

war, migrant workers seemed invisible to the average German. They failed to

register their suffering. The final section of the book deals with many of

these children as grownups, re-reading their childhood writings in total

bewilderment. Their adult selves have no memory of the childhood Nazis, the

naive followers of Hitler, the modern social democrat struggles to fathom his

childhood support of the final solution.

And finally some figures which I noted as I was reading this book. In a

week which saw the British death toll in Afghanistan (256) overtake the Falklands,

this is surely a reminder of the real impact of total war. By early 1942 2.5

million of the 3.3 million Russian prisoners taken by the Germans had died. On

July 24th 1943, 740 British planes bombed Hamburg leaving 10,289

dead followed by another 18,474 the following night. There was a respite until

July 29th when the next bombing raid killed a further 9,666 people.

In the final days of the war, Stargardt tells of a desperate column of 5000

prisoners, mostly Jewish women, being force marched from Konigsberg to

Palmnicken. Half died on the way, the rest were driven out onto the ice and

gunned down, not just by the Gestapo and SS, but by Volkssturm and Hitler

Youth. In the first four months of 1945 1.5 million German soldiers were

killed, a rate of 10,000 a day.

It is a reminder that whether you were German, Polish or Russian, Jewish,

Catholic or Protestant, there was no  escape

and no future.

escape

and no future.

A Partisan’s Daughter

Louis de Bernieres

Louis De Bernieres is one of my favourite writers, and I have followed

him from the South American series (The

War of Don Emmanuel’s Nether Parts, Senor

Vivo and the Coca Lord & The

Troublesome Offspring of Cardinal Guzman) through Captain Corelli and the masterful Birds Without Wings. All his

books are complex, full of characters, more stories than is probably good for

them, and exhibit a very Latin mix of myth, fantasy and all too real truth.

Which is why A Partisan’s Daughter is

a bit of a surprise. Just two characters have a number of conversations around

1980. Chris is a dull unhappy man. He is a desperately unhappy man, and

possible desperately dull and not particularly bright. He is as sad a character

as I can remember, trapped in his loveless, soulless, pointless marriage. He

meets a much younger girl, pretty, sexy, vibrant and despite her lack of years

she has lived many, many more lives than he. Trapped in lust he appears at her

house to hear the next episode of her life story, a story which may or may not

be true or partly true; we can never know. He wants to go to bed with her but

is scared to make the move, she wants to go to bed with him but fears that by

doing so she will lose him. Although we hear her voice, we are never sure who

Roza is, but we know enough to understand that this kindly, gentle man is

important to her. It all goes spectacularly wrong, of course. It becomes clear

that Chris is writing this memoir shortly before his own death, and that he

remained an unhappy man. Before she disappeared Roza left him a note in

Serbo-Croat – I thought you loved me.

His one and only opportunity of happiness he had lost. But worst of all, he

knew it.

In honesty I can’t describe this as ‘a masterpiece’ as many reviewers

have. It is too slight for my taste, but it was moving and affecting and so

very sad – but then, some of that is personal empathy! Worth a read - it won’t

take long - and worth a short ponder afterwards. It is a slight book, but

nonetheless a small contribution to an understanding of life, truth, stories

and happiness.

A Question of Upbringing

A Buyer's Market

The Acceptance World

Anthony Powell

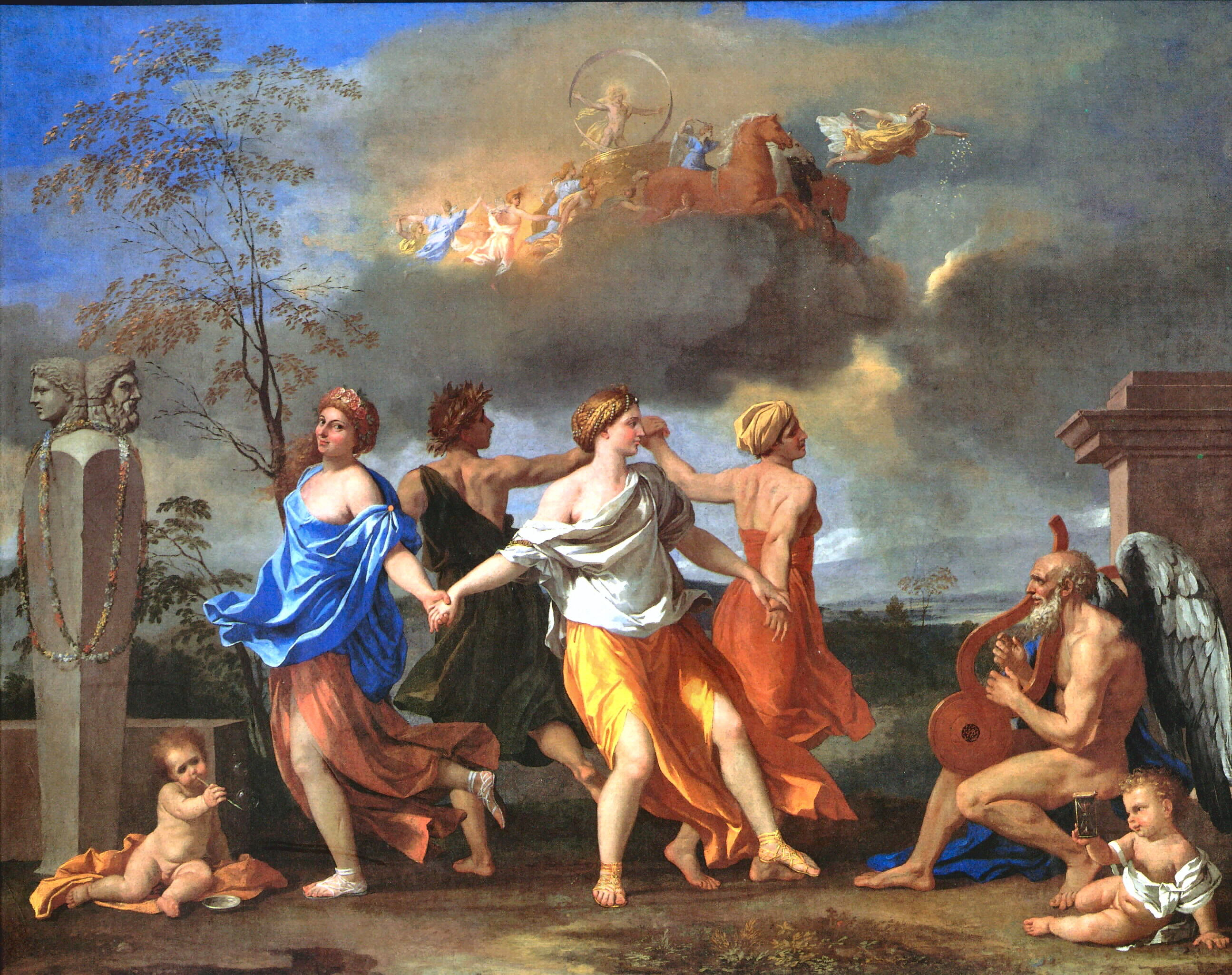

Anthony Powell’s 12 novel cycle

A Dance to the Music of Time appears to arouse tremendous enthusiasm in its

adherents. I know of people who insist on re-reading all the books every year,

and it is often quoted as one of the landmarks of the 20th century

novel. It is a book I have long been aware of, have heard bits and pieces on

the radio or TV, all making me aware that this was a project that needed to be

tackled.

Anthony Powell’s 12 novel cycle

A Dance to the Music of Time appears to arouse tremendous enthusiasm in its

adherents. I know of people who insist on re-reading all the books every year,

and it is often quoted as one of the landmarks of the 20th century

novel. It is a book I have long been aware of, have heard bits and pieces on

the radio or TV, all making me aware that this was a project that needed to be

tackled.

Spring, a volume comprising the first three novels of the cycle has been sitting on my shelf for a year and after Christmas I decided the time had come to embark on this great literary experience, A Dance to the Music of Time. Having now completed the first 700 odd pages I think I can be allowed a few early remarks.

A Question of Upbringing starts with the narrator (at this stage

Jenkins – we only learn his fist name in Book 2) in his final years at school,

around 1924 I guess. We meet  his immediate friends Templer

and Stringham, and a rather odd older boy called Widmerpool. We meet both

Templer and Stringham’s parents – though not the narrator’s. The book then

follows through to Oxford, where the wily don Sillery pulls all the strings

linking his protégés together. Whether Jenkins is one of these protégés is not

clear, but fellow students Members and Quiggin certainly are. A Buyers

Market sees these characters all in London starting to make their way in

the world. We follow Jenkins – Nick – as he regularly attends debutante dances,

Templer is a stockbroker, Stringham works for a rich and famous entrepreneur as

does Widmerpool later in the book. The first marriages take place and Nick,

through an old friend of his parents, frequents the edges of an artistic,

slightly Bohemian group of painters and radicals in Charlotte St. The

Acceptance World sees the group nearing 30, the familiar political patterns

prior to the Second World War are discernable with far left demonstrations and

far right meetings in clubs. Nick (finally) is having a love affair, Templer

and Stringham divorced, two of the group are published authors and all have

attached themselves to persons of wealth, influence and power.

his immediate friends Templer

and Stringham, and a rather odd older boy called Widmerpool. We meet both

Templer and Stringham’s parents – though not the narrator’s. The book then

follows through to Oxford, where the wily don Sillery pulls all the strings

linking his protégés together. Whether Jenkins is one of these protégés is not

clear, but fellow students Members and Quiggin certainly are. A Buyers

Market sees these characters all in London starting to make their way in

the world. We follow Jenkins – Nick – as he regularly attends debutante dances,

Templer is a stockbroker, Stringham works for a rich and famous entrepreneur as

does Widmerpool later in the book. The first marriages take place and Nick,

through an old friend of his parents, frequents the edges of an artistic,

slightly Bohemian group of painters and radicals in Charlotte St. The

Acceptance World sees the group nearing 30, the familiar political patterns

prior to the Second World War are discernable with far left demonstrations and

far right meetings in clubs. Nick (finally) is having a love affair, Templer

and Stringham divorced, two of the group are published authors and all have

attached themselves to persons of wealth, influence and power.

The book(s) is both less entertaining and more interesting than I imagined. Frankly, as a plot, it is pretty pathetic, though as the series developed I did start to gain some mild interest in the fate of this vast array of characters - the blurb says over 300 characters, which entirely believable. The writing is good, but stilted by modern standards and verbose. A room will get 2 pages of description a new character 4 pages, a painting another 2 pages a poem a page. Indeed, painting and pictorial analogy is a large part of this book (the title being taken from Poussin's 'A Dance to the Music of Time'), though clearly the reader is expected to be at least familiar with French, German, Italian and Latin.

And this is the interesting part, for as a ‘source’ for the time I find it fantastically interesting. The modes, language, assumptions are of absorbing interest. Is it reasonable that so many of Nick's friends from school and College are powerful and famous? Entirely, I suspect, though the first book identifies endless class differences. Templer remarks that he won't see much of Stringham when they leave school. Templer is rich, but not that rich. Others male friends and of course potential female marriage partners are subject to a painstaking analysis of class that seems genuinely shocking today. These rich young men party hard, but do take work seriously. They marry young and get divorced. By the close of the third book both Temper and Stringham are divorced while Nick is having an affair with an estranged wife. Perhaps this just shows up my lack of knowledge of those inter-war years, but for this alone I have been quite riveted.

So while I doubt I'll be re-reading the series as a mater of course I will move on fairly quickly to the next three novels. The characters have, despite it all, got under my skin, and I wonder what will become of them all. And what I may learn of this intellectual elite as the war looms.

Exit Ghost

Philip Roth

I don't read a great deal of

contemporary American fiction, generally keeping to English (and Commonwealth)

and European writers. It is noticeable that when I do, the subject matter seems

always to be the same: literature. Almost all the American novels I've read

'recently' (remembering a three-year gap!) have as their subject, what is

literature, what is a novel, what is the act of writing about. Although

ostensibly about the aging process for me this concise and superbly written

book is still about literature and the act of writing. The aging novelist

Nathan Zuckerman returns to New York after living for 11 years as a virtual

recluse. He is suffering from prostate cancer and Roth spends a great deal of

time explaining the rituals an elderly sufferer must go through to obscure

their incontinence. He is impotent as well, and understandably depressed. And

yet.... after less than a day back in the centre of things he is flirting with

an attractive young woman, he is combating a young literary lion and

rediscovering past events from another aging and sick member of the writing

elite. But then there are more weaknesses. He is losing his memory. He can't

recall conversations. He must write his ideas rapidly before they disappear. He

is trapped in this spent body, yet his desires are the same as ever, to conquer

women, to triumph over competitors, to right wrongs.

I don't read a great deal of

contemporary American fiction, generally keeping to English (and Commonwealth)

and European writers. It is noticeable that when I do, the subject matter seems

always to be the same: literature. Almost all the American novels I've read

'recently' (remembering a three-year gap!) have as their subject, what is

literature, what is a novel, what is the act of writing about. Although

ostensibly about the aging process for me this concise and superbly written

book is still about literature and the act of writing. The aging novelist

Nathan Zuckerman returns to New York after living for 11 years as a virtual

recluse. He is suffering from prostate cancer and Roth spends a great deal of

time explaining the rituals an elderly sufferer must go through to obscure

their incontinence. He is impotent as well, and understandably depressed. And

yet.... after less than a day back in the centre of things he is flirting with

an attractive young woman, he is combating a young literary lion and

rediscovering past events from another aging and sick member of the writing

elite. But then there are more weaknesses. He is losing his memory. He can't

recall conversations. He must write his ideas rapidly before they disappear. He

is trapped in this spent body, yet his desires are the same as ever, to conquer

women, to triumph over competitors, to right wrongs.

The main wrong he is determined to right, or to be more exact to prevent being wronged, is the memory of E. I. Lonoff, an obscure and forgotten writer who was Zuckerman's original inspiration. He is 'threatened' with a biography, one that will expose his personal life, which will attempt to explain his oeuvre by reference to mundane real events. Zuckerman is determined to prevent this terrible occurrence. He writes desperately, He and She dialogues of flirtation but we do not know if they represent real events or imagined ones. There is an unpublished novel by the iconic Lonoff yet Zuckerman leaves it in the bin, unread. Lonoff's last lover laments that the novel killed him because he had to reveal too much. Is there a 'truth' revealed in the novel or is it intellectual posing?

These two struggles, the man and his failing body, and the truth of literature interweave every moment of the book. The object of Zuckerman's flirtations is a writer, as is her husband, as is Lonoff's lover. Eventually defeated, Zuckerman returns to obscurity, hides from these battles he is no longer confident of winning, retreats to writing even though he can't remember actually doing the writing, he leaves the City to live while he goes to die. Not a laugh a minute, as you will have gathered from this short review, but a very well written, economical book that pulls no punches. Very American, it probably encapsulates their issues more than ours, but still asks stark questions without sentimentality.

Black Swan Green

David Mitchell

I remember struggling to

describe David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas on this page a few years ago. In

the end I decided it was closest to science fiction but whatever it was, it was

a stunning and great book. Having finally picked up its successor there is no

such difficulty. It is astonishingly ‘ordinary’ – a rights of passage story.

The year is 1982, Jason is 13 and all sorts of things happen to Jason over the

year. There is nothing ‘clever’ about its construction, it is a very standard

format, but very well done.

I remember struggling to

describe David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas on this page a few years ago. In

the end I decided it was closest to science fiction but whatever it was, it was

a stunning and great book. Having finally picked up its successor there is no

such difficulty. It is astonishingly ‘ordinary’ – a rights of passage story.

The year is 1982, Jason is 13 and all sorts of things happen to Jason over the

year. There is nothing ‘clever’ about its construction, it is a very standard

format, but very well done.

As with any book like this creating the period is vital, and generally Mitchell does this excellently. It is a good year to focus on – Thatcher is still new, the recession is biting, the Falklands war arrives from nowhere. In Black Swan Green Jason’s sister goes to University, his stammer is revealed to his class mates, one of the village youth is killed in the war and his parents break up. He meets some more mystical adults – the poetic daughter of a classical composer, a mysterious old woman in the woods and some gypsies – and he starts to see girls in a different light.

Status is all. At the start Jason is middle-ranking kid, he is briefly elevated to high status child, but is then relegated to the 'lepers'. His position in the school male hierarchy is everything, and colours every event in his life. Interestingly by far the most sympathetic figure in the book is a 'leper'. Dean Moran accepts his position with good grace and come across as someone who will lead a happy and successful life, even though he has to fail at school as part of his role.

In other words, nothing world shattering happens, a boy grows up a bit or possibly a lot. The first nine tenths of this book are absolutely delightful. Beautifully written through Jason’s eyes, bringing back memories of my own – from 1982 and earlier – and all very solidly believable. I was less convinced by the ending. While it is not a ‘happy ending’ it was certainly an heroic one. Suddenly Jason was able to wreak revenge on his bullying tormentors and he even got the girl. At one stage I was really worrying that it was going to turn into an early McEwan and the school bullies would all suffer terrible and humiliating tortures, but it didn’t get quite that bad. Nonetheless, Jason’s sudden ability to piece together the advice he had received from various sources to best the bullies did seem a little hard to match with the likeable, arty figure we had journeyed though the fist ten months with.

So a really good book, an enjoyable read, but unless there was a point I missed, a rather unsatisfactory ending

A Most Wanted man

John le Carré

Time to read my first novel for 15 months... and I pick up the latest le care which has lain on the ‘to read’ pile since Christmas. There has recently been a plethora of twentieth anniversary programmes celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall, and this is a reminder that not everyone enjoyed the end of the Cold War. Le Carré’s books framed the war for many, creating a language which was convincing enough to become accepted credence. The official chronicler of the East West confrontation struggled with the peace. A couple of poor books followed as he struggled to find his feet, but the Constant Gardener showed that he could write outside of Europe and outside of the security agencies, and he has not looked back.

Here we are back in the Germany he knows so well, a contemporary story which set in a world arguably just as complex as his old times. A young refugee comes to Hamburg, a strange damaged young man from Chechnya. Lots of people are interested in him – the German security services, the British, the US. Is he a terrorist, a pawn in the ‘War of Terror’? A civil liberties lawyer is determined to keep him out of the clutches of the German Police and a Scottish banker has to confront an embarrassing past as a direct result of his arrival.

Strangely perhaps the one character we never really get to know is the young man himself – Felix or Issa or Ivan remains a mystery as the powers circle around him. Annabel, the lawyer, is more than a little in love with this mysterious stranger – is he really as Islamic as he seems? As altruistic? Chechen even. And Brue, the banker is more than a little in love with Annabel, casting aside his usual reserve to back the girl’s attempts to protect the stranger. For the Germans Issa is a route to bigger fish, to the British a pawn to be played which keeps them in the game and for the Americans an evil monster.

Le Carré is again gaining a confidence in his portrayal of the complex world where former KGB officers are the mafia, where the Western spies fight over the turf of Europe and every Islamic figure is a figure of suspicion and intrigue. He seems to have developed a bitter anger at the US which pervades this and the last le Carré I read – Absolute Friends – making this a furious assault on the absurd ‘War of Terror’. A brilliant read, intriguing page-turner and a deep insight into the tiny stories that make up the backdrop to the news this is a first class book.

Ground Control

Anna Minton (Penguin)

Getting

the negatives out of the way first, this is not a well edited book. It is

endlessly repetitive, confusingly structured, and the tone shifts radically

between a fairly academic style and simple reportage. It is hard work trying to

find a coherent narrative, though I will in a moment attempt to do just that.

Getting

the negatives out of the way first, this is not a well edited book. It is

endlessly repetitive, confusingly structured, and the tone shifts radically

between a fairly academic style and simple reportage. It is hard work trying to

find a coherent narrative, though I will in a moment attempt to do just that.

On the other hand the information she has is fascinating, often shocking and it is all slightly perturbing that I didn’t know much of this stuff. She makes a persuasive case against the government on a number of different levels.

The book is essentially about ‘public space’, though it also spends a lot of time looking at housing, surveillance and policing. Analysing her analysis I think she covers the following strands:

· the privatisation of public space

· the growth of high security as an integral part of private space

· the negative impact of surveillance culture

· the equating of financial return with well being

· secretive governance.

She starts with an account of the

very recent rise in private ‘public’ space, suggesting that its genesis was in

Docklands. She then details how since New Labour came to power, increasingly

public developments, in particular shopping malls, have moved towards private

ownership. The latest classic example is Westfield, a huge anonymous temple to

shopping, but owned not by the council but by the building developers. The

business model is not predicated on Westfield being a successful shopping

centre, but on the land on which it is built growing in value. While there is

some instinctive realisation that a shopping mall with doors could be private,

but the next phase of regeneration (she mentions Broadgate in the City,

Manchester and Liverpool 1) do not have doors, but are still private spaces.

After the IRA bomb devastated the centre of Manchester, it has been redeveloped

by a private public partnership with

the result that the whole of the centre of the city is run by a company called

(imaginatively) Cityco, not the local council. Does this matter? Well, in one

very important sense it does. Exchange square an Piccadilly Gardens are not

part of the city and do not share the same rules. The company can decide who it

wants to visit it and what they may wish to do. Demonstrating, for instance

either against the war in Iraq or the presence of animal fur in a shop is

explicitly prohibited. While a city space is inclusive, a private space is

exclusive and Cityco do not want non-shoppers in their space. This is, she

suggest the main reason why Manchester is the ASBO capital of England, serving

huge numbers to restrict access in the city centre of those who do not have

money to spend – the homeless, the mentally ill, NEETs youth in general, and so

on. Being a private space it has its own uniformed ‘security’ staff to enforce

its own rules. It uses the plethora of CCTV cameras to ensure that people like

my cameraman friend Graham never gets to film anything. They do not like

photographs and particularly not video, unless they control it. And it is THEY,

not US.

with

the result that the whole of the centre of the city is run by a company called

(imaginatively) Cityco, not the local council. Does this matter? Well, in one

very important sense it does. Exchange square an Piccadilly Gardens are not

part of the city and do not share the same rules. The company can decide who it

wants to visit it and what they may wish to do. Demonstrating, for instance

either against the war in Iraq or the presence of animal fur in a shop is

explicitly prohibited. While a city space is inclusive, a private space is

exclusive and Cityco do not want non-shoppers in their space. This is, she

suggest the main reason why Manchester is the ASBO capital of England, serving

huge numbers to restrict access in the city centre of those who do not have

money to spend – the homeless, the mentally ill, NEETs youth in general, and so

on. Being a private space it has its own uniformed ‘security’ staff to enforce

its own rules. It uses the plethora of CCTV cameras to ensure that people like

my cameraman friend Graham never gets to film anything. They do not like

photographs and particularly not video, unless they control it. And it is THEY,

not US.

Anna goes back to Victorian London, when the poorer parts of the city were delineated from the wealthy parts by a private security service with gates, keeping the West End pure from the poor in the East, and how these lines of division were torn down as part of the democratisation of London. Now we see these very same divisions, between private and public, between rich and poor being re-introduced.

The question why cities are increasingly becoming privately owned is more conjectural, but it appears to be about money and profit. This ‘regeneration’ ensures high profits for developers and councils alike, the only losers being the citizens themselves who gain a shopping centre, but lose freedoms and privileges.

Her view is that in most cases she has looked at ‘regeneration’ is about taking an area of depressed property prices and giving the market a push, so creating a volatile market in which high returns can be made by the developers (and probably the local council). The problem with this approach is that the local people are not helped by this (having been now priced out of their own market) and indeed actually suffer greater destitution as a result of this ‘regeneration’.

An

example of this approach – and I may well write something separately on this –

is the Housing Market Renewal Pathfinders. Briefly, this is a government policy

which aims to demolish good solid but working class Victorian homes and replace

them with modern apartment style housing blocks. The aim is to take areas of

low property prices (clearly, and unquestionably a bad thing) and replace them

with the sort of homes young professionals want, thereby increasing the market

value. The council takes the grant, the developers (often these days a part of

the social housing associations) take the profits - anything between 500% and

1000%. The poor communities are split up and scattered and new middle class

groups move in. Over £1billionof our money has gone into this appalling piece

of social apartheid. If you look at the web sites for the 9 pathfinder areas

they only talk of ‘refurbishing’ the housing stock, but the Housing Committee

report on the projects make it clear that around half a million houses have so

far bee n demolished. Rather less have been built – what with the recession and

the fall in property prices.

An

example of this approach – and I may well write something separately on this –

is the Housing Market Renewal Pathfinders. Briefly, this is a government policy

which aims to demolish good solid but working class Victorian homes and replace

them with modern apartment style housing blocks. The aim is to take areas of

low property prices (clearly, and unquestionably a bad thing) and replace them

with the sort of homes young professionals want, thereby increasing the market

value. The council takes the grant, the developers (often these days a part of

the social housing associations) take the profits - anything between 500% and

1000%. The poor communities are split up and scattered and new middle class

groups move in. Over £1billionof our money has gone into this appalling piece

of social apartheid. If you look at the web sites for the 9 pathfinder areas

they only talk of ‘refurbishing’ the housing stock, but the Housing Committee

report on the projects make it clear that around half a million houses have so

far bee n demolished. Rather less have been built – what with the recession and

the fall in property prices.

Increasingly private estates are ‘gated’. Anna suggests that while this used to be mark of exclusivity, it has become very mainstream. Increasingly all modern housing developments are gated and include widespread security apparatus. This is again a public/private space. Rules and regulations abound in these gated enclaves (rules on what you can cannot do in your gardens, how you paint your doors looking after gardens etc, etc), with private security, private refuse collection and so on. She suggests that the reason for this recent proliferation of gated estates is the police. They advocate a policy called ‘Designed for Security’ which demands gates, CCTV, grills on windows and so on. Increasingly it is impossible to get planning permission for non-gated developments as the police will oppose them.

Anna then veers off to psychology to examine if CCTV cameras, gated enclosures and security guards actually achieve anything. As we know, people are more afraid of crime than ever, even though crime has been falling for 15 years. For me, the most persuasive part of her analysis was her account of ‘the stranger’. She suggests there are two ways of viewing a stranger. Either the stranger is danger, a threat; this is the view so often espoused in the press, and it is this view which the gated ‘Designed for security’ approach is designed to deal with. Inside the gated enclosure the stranger is obvious, is excluded, is eliminated. The other view, of course, is that strangers represent safety. Do you feel more vulnerable walking home late at night in a quiet and deserted area, or down a busy well frequented nightspot? In a healthy society (and here Anna shares my Eurocentric prejudice) such as on mainland Europe, city centres are full of people walking, talking, socialising, window shopping and they act as their own police, ready to intervene as citizens if there is trouble. In France or Spain or Italy the presence of strangers prevents most ‘trouble’. So the very act of designing out ‘strangers’ actually makes people more unsafe. Another example is that people are less inclined to intervene in areas where there is CCTV; the presence of this ‘higher authority’ makes people take less personal responsibility for what is going on. The CCTV camera people will deal with the issue, we don’t need to bother. She goes on to suggest that it doesn’t even make people feel safer, since the security habit grows and people feel they need even more security – amusingly she talks of gated communities with gated houses within.

In her conclusions she lurches again for psychological explanation and gives a long account of the way in which increasingly traffic signs, warnings and restrictions are removed forcing drivers to take greater responsibility with a resultant fall in accidents. A very good analogy, but strangely left for her conclusion.

Her thesis is that all too often ‘regeneration’ - which we might think is a way of improving an area for its inhabitants - is simply used to increase property prices and allow developers (and councils) make bigger profits. There is no ‘trickle down’ effect, and in many cases original residents feel (or indeed actually are) excluded from their own areas. This is all justified as ‘regeneration’, market renewal, the creation of better spaces, safer streets - but only for a chosen group, not for all and possibly not for those who you might think were supposed to be the beneficiaries.

Despite its scattergun approach, this is an impressive condemnation of the way this government has operated in its core area. It shows in great detail one of the mechanisms by which the rich have got richer at the expense of the poor, the ways in which this society has become more divided and more scared, worried and unhappy. It pulls away any lingering hopes that there is something decent operating at the heart of New Labour, for if they can attack the residents of the East End or Liverpool, transferring wealth to big business, then there really is no point. It is a tragedy, but it is important that such tragedies are recorded, written down and analysed. I am at heart an optimist, and let us hope that at some stage the left, the liberal establishment or the progressive movement learns from this desperate tale.

I have since had the following comment from Graham Dougall:

I appreciate the mention in your book review. There are so many places people walk through these days totally unaware that they are on private property. I have worked with a number of directors/producers who think I am being awkward when I ask if they have sought permission to film.

Then when you are in real public space you run into the police or more especially their Cheap Substitutes, the Community Support officers, who have a limited grasp of what the laws are. A classic was the Austrian tourists picked up for photographing buses: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/apr/16/police-delete-tourist-photos

One of the things I wanted to do if I had been selected for the Fourth Plinth was to photograph myself as part of the 'I'm a Photographer Not a Terrorist' campaign: http://photographernotaterrorist.org/. There was a great angle in front of a prominent CCTV camera in the top corner of the Square. Perhaps I should get this T-shirt: http://www.redmolotov.com/catalogue/tshirts/all/iamnotaterroristbearded.html

Some Medieval Good Reads

A good example of how a small book but a big argument can have tremendous impact is Henri Pirenne's Mohammed and Charlemagne. The essence of this book is that the 'Fall of the Roman Empire' was not caused by the invasions of Germanic tribes but rather by the rapid rise of Islam. The new religion took control of the Mediterranean turning it into a 'Muslim lake' and breaking contact between Constantinople and Western Europe. The focus of the West had to move away from the sea and found its new lead in Charlemagne and the empire of the Germans. It is a challenging thesis, thoroughly well argued and hugely entertaining. In all probability every historian in the world agrees with parts of his thesis and disagrees with others, but it is a classic book which changes one of the central paradigms of medievalism.

Rather more up to date is R. I. Moore's The Formation of a Persecuting Society. This suggests that persecution was not a 'norm' of medievalism, nor that the persecutions of heretics or Jews simply a series of separate responses to specific situations but rather a new pattern of society consciously evolved and still with us. Persecution is not a force of nature but a deliberate act of will by the elites of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Again, a short book arguing a coherent case, you may agree or disagree with his argument, but it will both challenge and entertain you to do so.

Finally I can recommend absolutely anything by Peter Brown. Few scholars can claim to have invented an era but Brown has done just that with 'Late Antiquity', the awkward time before medievalism and after the 'fall' of Rome. His books are probably the best written I've read in the past two years, and his gentle sociological probings of early Christianity, examining the cult of saints for instance, or exploding the myths surrounding popular Christianity are absolute joys. His sociological approach works perfectly in a time which is sufficiently ancient with difficult and sparse sources, and his analysis of Christianity as 'another' cult works perfectly. But mainly, he is a thoroughly enjoyable read, and his chosen area, the formations of modern Christianity and its place in the world of the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries absolutely fundamental to all that follows. His small book The Cult of Saints is a good start, and I have bought the rather larger The Rise of Western Christendom for reading when I get used to a bit of leisure time.