Medieval

History

The Mediterranean

in Late Antiquity

A colloquium held

by the Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity

May 15th

2010

I thought it would be interesting to

participate in some Medievalism, and one of our course leaders send out details

of this colloquium. Admittedly it was concerned with Late Antiquity rather than

Medievalism as such, but the jury is still out as to whether there is really a

difference. Indeed, it was one of the themes of the day that speakers were very

unsure about their branch of history, being not at all confident they

themselves knew what Late Antiquity was. The agenda was essentially that of the

Medieval Mediterranean course (see

below), and although looking at particular issues the overarching idea was to

look at the ‘long durée’ from Latin, Greek and Arabic sides. Appropriately the

first session was chaired by Peregrine Horden, one of the writers of The Corrupting Sea, the unfathomable

book which framed that course. The first session looked at Christianity and

state power in Rome and Constantinople. Chris Kelly’s paper was based on a

sermon of John Chrysostom about the Empress dancing in front of relics while

Peter Heather didn’t so much deliver a paper as mused over issues of later

Western Christianity. The second session was the Arabic one, and although far

from easy, it was very intriguing. Nicola Clarke gave a paper about writing the

history of the invasion of the Iberian peninsula which I wanted to listen to,

but her delivery was frankly so poor it was hard to engage with while Philip

Wood’s paper on ‘Jacobite’ church in the Levant I just didn’t understand, but I

was intrigued. I have come across the use of the word Jacobite in many

contexts, but never this one. As far as I could tell he was referring to a Monothysite

sect in the Arabic lands before Islam. Lots to look at when time permits. The

final two papers was perhaps the most entertaining of the day – Eileen Rubery

using some very faded remnants of paintings in a ruined church in Rome and

suggesting this was a part of the argument between Rome and Constantinople over

acceptance of the Chalcedon position around 540AD. This was really well illustrated

with pictures and diagrams making it an ideal after lunch session. This left by

far the most entertaining speaker of the day, and organiser of the even Peter

Ball to talk about how the inhabitants of Constantinople were not Byzantines

but Romans, inhabiting Rome and running the Roman Empire. We didn’t stay for

the discussion session, feeling it was time to get some air and see Oxford –

and indeed pop into the newly refurbished Ashmolean Museum.

I thought it would be interesting to

participate in some Medievalism, and one of our course leaders send out details

of this colloquium. Admittedly it was concerned with Late Antiquity rather than

Medievalism as such, but the jury is still out as to whether there is really a

difference. Indeed, it was one of the themes of the day that speakers were very

unsure about their branch of history, being not at all confident they

themselves knew what Late Antiquity was. The agenda was essentially that of the

Medieval Mediterranean course (see

below), and although looking at particular issues the overarching idea was to

look at the ‘long durée’ from Latin, Greek and Arabic sides. Appropriately the

first session was chaired by Peregrine Horden, one of the writers of The Corrupting Sea, the unfathomable

book which framed that course. The first session looked at Christianity and

state power in Rome and Constantinople. Chris Kelly’s paper was based on a

sermon of John Chrysostom about the Empress dancing in front of relics while

Peter Heather didn’t so much deliver a paper as mused over issues of later

Western Christianity. The second session was the Arabic one, and although far

from easy, it was very intriguing. Nicola Clarke gave a paper about writing the

history of the invasion of the Iberian peninsula which I wanted to listen to,

but her delivery was frankly so poor it was hard to engage with while Philip

Wood’s paper on ‘Jacobite’ church in the Levant I just didn’t understand, but I

was intrigued. I have come across the use of the word Jacobite in many

contexts, but never this one. As far as I could tell he was referring to a Monothysite

sect in the Arabic lands before Islam. Lots to look at when time permits. The

final two papers was perhaps the most entertaining of the day – Eileen Rubery

using some very faded remnants of paintings in a ruined church in Rome and

suggesting this was a part of the argument between Rome and Constantinople over

acceptance of the Chalcedon position around 540AD. This was really well illustrated

with pictures and diagrams making it an ideal after lunch session. This left by

far the most entertaining speaker of the day, and organiser of the even Peter

Ball to talk about how the inhabitants of Constantinople were not Byzantines

but Romans, inhabiting Rome and running the Roman Empire. We didn’t stay for

the discussion session, feeling it was time to get some air and see Oxford –

and indeed pop into the newly refurbished Ashmolean Museum.

So an excellent day, some good speakers (and some less good) and plenty

of new ideas to explore. Just what I needed really, new ideas to explore!

The Course:

After a successful and hugely enjoyable year on the Politics, Philosophy and History BA course (PPH) I very cheekily applied to go on to an MA course in Medieval History. Valid, as I have a first degree.... but in Physics, and haven’t actually done any history since ‘O’ level. Despite pontificating away in my chat with the course leader John Arnold about absolute bollocks he accepted me and so started a life-changing experience.

The course consisted of the ‘Core Course’ + four other modules, each assessed by a 5,000 word essay and a final 15,000 word dissertation. All teaching was in two-hour seminars. This changes the balance from traditional lectures since you do the reading first and test you understanding in the seminars, often a challenging experience.

The first term was the Core Course, Power and the Middle Ages, an introduction to techniques or studying a period when sources are never plentiful and often non-existent. For the Power and the Middle Ages course I decided to write (a rather challenging choice, I agree) an essay on a female mystic called Angela of Foligno and subject her case to a Foucauldian analysis. I had got used to 70+ marks doing PPH and the resultant 57 was a bitter disappointment, though not as stunning as the first remark from the marker: You have not even scratched the surface of the reading.... I had never read as much in my life as I did for that essay, so this was a blow. I admit my morale did suffer for a while and I wondered if I had over-stretched myself. But in the end, I just had to accept that this was the level I wanted to achieve, so I upped the level of reading!

The Modules:

Power and the Middle Ages

Essentially an introduction to some of the techniques of study. The sources in the Middle Ages are invariable limited and difficult to interpret, so medievalists have to utilise other ‘tools’ from sociology, anthropology and so on. It also introduced us to some of the issues about sources, language, palaeography, the idea of topos and so on. It also taught us never to use the word feudal as this would bring down on us the wrath of Susan Reynolds, an elderly but indefatigable opponent of the concept.

Heresy in the Middle Ages

As readers of this website will know, this was one of my starting points. Here at least I knew the secondary literature. We started by looking at the first instances of reported heresy in the west in the Middle Ages, then led us through the build up of ‘Catharism’, the Albigensian Crusade and the inquisition. The first seminal moment was about week 5 when John told us: you have now read all the existing texts from the period. You know as much as the historians whose books you have read. They have no more to go on than you have just read. This was a shock, but a very, very good one. I can never read a ‘Cathar’ book in the same light. In fact, I struggle to read any of my ‘Cathar’ books given this new knowledge. When you read in O'Shea's 'Perfect Heresy', the source of some of my existing ideas on Catharism, about the Cathar Council of St Felix-de-Caraman in 1167 an account of a meeting between the leader of the absolutist Church of Drugunthia and the Cathar Bishops from the Laurgaise which created two new bishoprics and re-consecrates the assembled bishops in the ‘absolutist’ ordo, from the ‘moderate’ ordo they previously followed, the problem is that I have now read the document. Suffice it to say, it just does not say that, however boldly you interpret it!

The

Medieval Mediterranean

The

Medieval Mediterranean

This was a difficult course, looking at the role of the Mediterranean in the early period specifically through three new books (all huge) which took very broad principles to analyse the impact of change across almost 1000 years. The first difficulty was the reading – Caroline Goodson frequently setting us 400-500 pages a week to read. Amazingly, as a group we seemed to manage to read enough between us to keep the seminars lively and give the impression we all knew what was going on. Secondly, it was difficult. One week we are talking trade through numismatics, another comparing Braudel’s concepts of the long dureé to the pre and post fall of the Roman empire, the archaeology of Amphora (large pots for transporting olive oil, wine and fish sauce around the empire), far too many weeks on the impact of terrain on history and lots about transport across the sea. Nonetheless, the central question: did the average ‘peasant’ in southern France or Anatolia or Tuscany actually notice the ‘Fall of the Roman Empire’ is a serious one. W the Fall of the Roman Empire really the great event brought down to us by the classical historians?

Memory and History in the Middle Ages

In the end, perhaps the most enjoyable of the courses. It sstudied an earlier period than I had expected to be comfortable with – Bede through Charlemagne to Alfred (600-900) – but did have an interesting concept. This was not about our ‘remembering’ of the past but of the ancient past ‘remembering’ the even more ancient past. So it was how Bede’s English remembered the Romans, how Alfred looked to the writing of the Carolingian court. It was an opportunity to discover how wonderful Beowulf is, get to grips with the biographies of Charles and Alfred. A thoroughly entertaining course.

Ancient Political Thought

On the other hand I took this understanding it would be hard and was not disappointed! Just as the political philosophy module way back in PPH was the moment when I felt embarrassed by my lack of knowledge – of Hobbes, Lock and Rousseau - I remained very ignorant of classical philosophy. This course took us through Plato, Aristotle, the Cynics through to Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. Luckily we had perhaps the most gifted teacher in Caroline Humfress, and this was the most directly taught course we did. In ‘Memory’ we sat in a circle discussing the texts we had read, but here we absorbed Caroline’s words punctuated with questions and complex diagrams on the board. At the end of a seminar I felt, if only briefly, that I had gained some philosophical understanding. It was hard, but I am delighted I did it!

The Essays:

While 5000 words doesn’t seem a great deal, the writing of each of these essays has been quite an event. I have certainly attempted to do a level of original research with mixed success, but have been consistently complimented on my use of primary sources. My essay on the Heresy course attempted to evaluate the claims that Catharism spread from the Albanian heresy of the Bogomils (I concluded that it didn’t because signs of dualism appeared in Western Europe too early to fit with the evidence of Bogomilism from the East), while for Mediterranean I wrote an essay evaluating the origins of the wealth of a Carolingian monastery in Northern France (St Riquier) and what it tells us about our ideas of commerce in the eighth century.

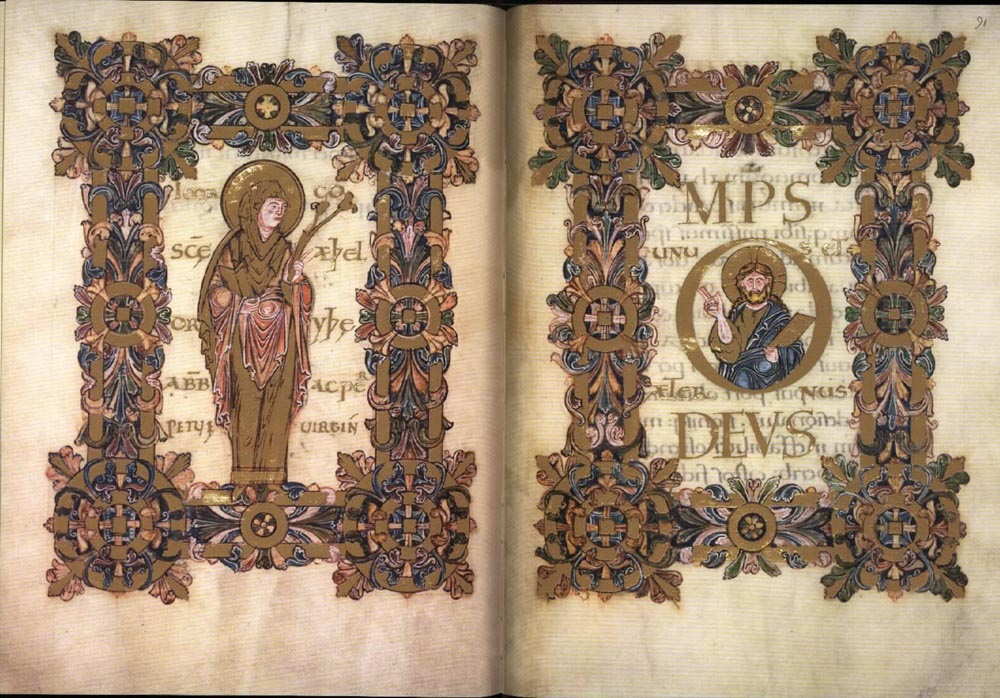

Memory stimulated my most successful essay, a comparison of the ways in which contemporary writers from the sixth to the twelfth centuries interpreted the life of St Aethelthryth and what it told us about them rather than her. The final essay was an analysis of how Justinian’s re-discovered Roman laws influenced the marriage laws as they were shaped laid down by Gratian in the Decretum and later by pope Alexander III in the Decretals.

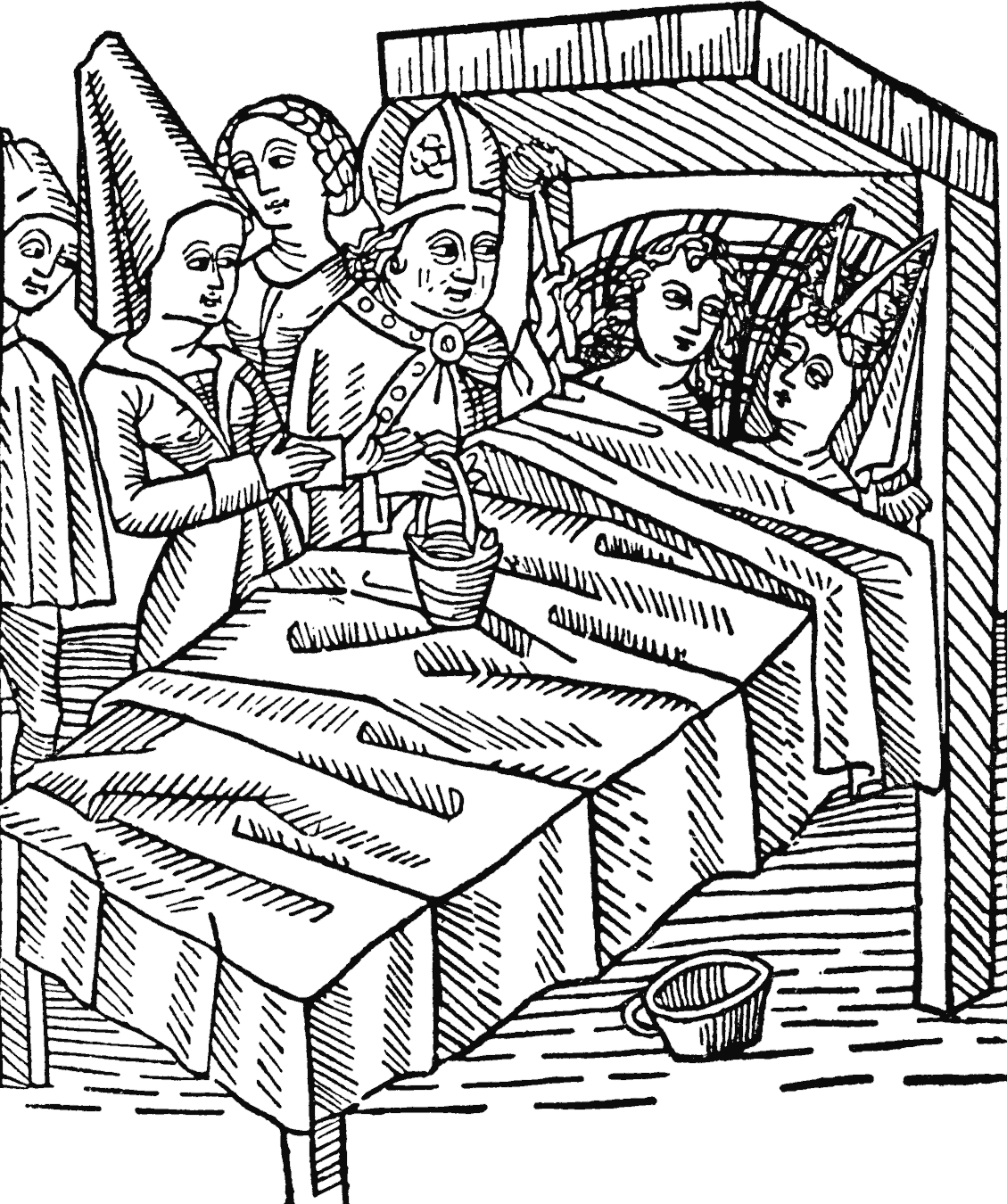

Which brings us to the final act, the dissertation entitled The Imposition of Clerical Celibacy in England following the Conquest. As a part of this project I have made an attempted to decide whether each bishop in England between 1070 and 1195 was or was not sexually active, and also collated references to all cathedral canons who might have been sexually active over the same period. So although ‘only’ a 15,000 word essay, I have managed to include a 7,000 word appendix!

The Result:

A couple of days before Christmas we eventually received our results, and I did manage to get a Distinction - with 75% for the Dissertation and the Aethelthryth essay upgraded to a slightly staggering 80%. All in all this represents a stunning return on my gamble and I am absolutely delighted.

So what now? Despite an undeniable temptation, I don’t see much point at my age in ploughing on towards a PhD. However, to make a real contribution in local history or any further limited studies, I really need to work on my Latin, particularly Medieval Latin and perhaps some palaeography so I can actually interpret manuscript evidence should I get an opportunity to read it. So I’ll stick to some small scale courses in those for the moment. I can also look towards trying to get some of this work published or delivered in papers.

Once I can face it, I will re-interpret the above essays for a non-academic audience and put them on the website. But before all else, I need to revisit my naive ramblings about Catharism and attempt to bring these more in line with my current knowledge.